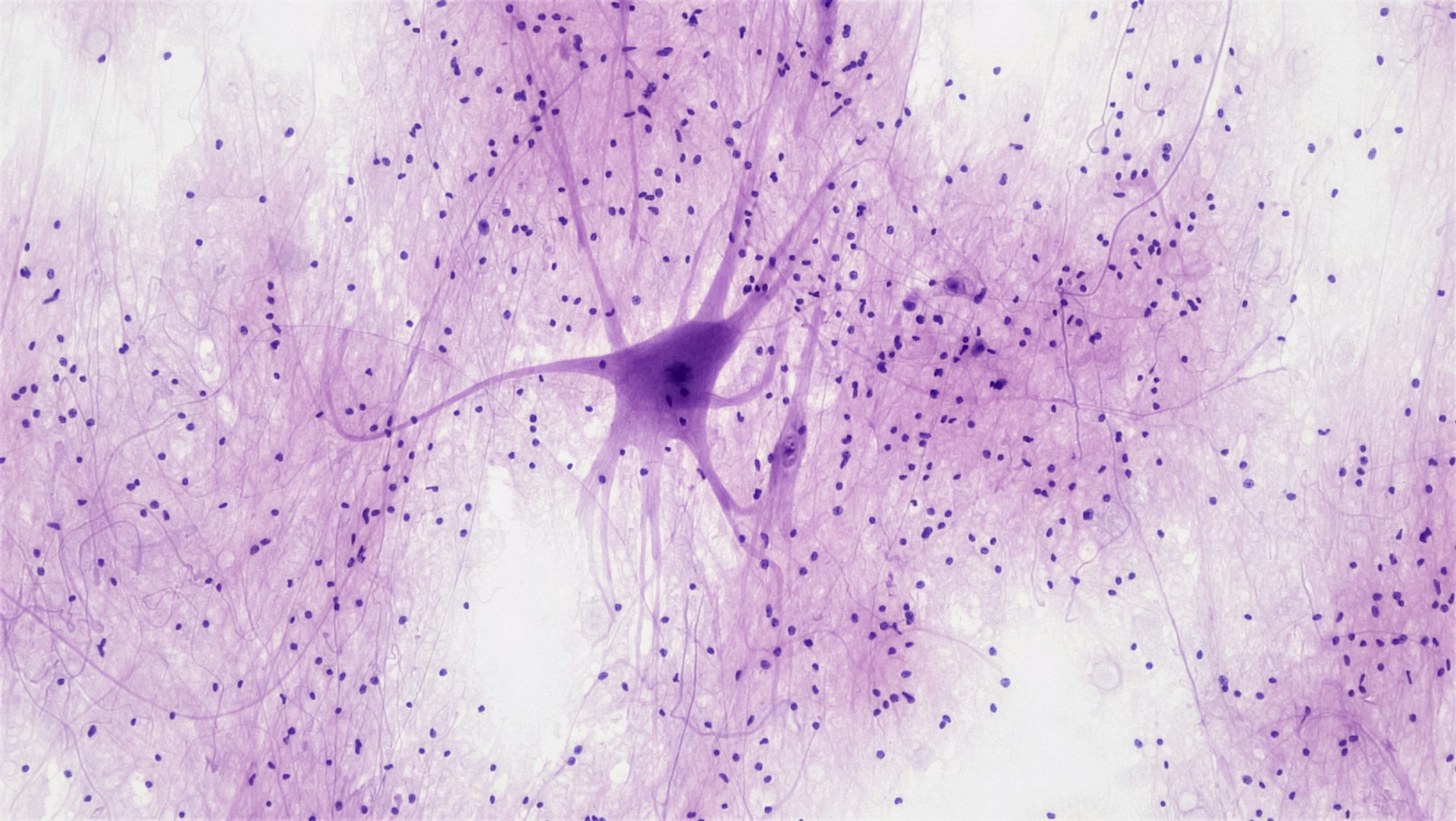

Image: Scan of a part of nervous tissue. Bioscience Image Library, Fayette Reynolds.

Image: Scan of a part of nervous tissue. Bioscience Image Library, Fayette Reynolds.

During my final year of my computer vision degree, I wrote a paper titled “Know Your Neighbour”. In it, I highlighted how techniques in machine learning can be used to improve the efficiency of what’s called “3-dimensional neuron segmentation”, i.e, the process of identififying neurons in 3D space. Both me and my supervisor were very happy with the results, so I decided to write this blog, explaining what it is, how it works and what implications it can have for the future of neuroscience.

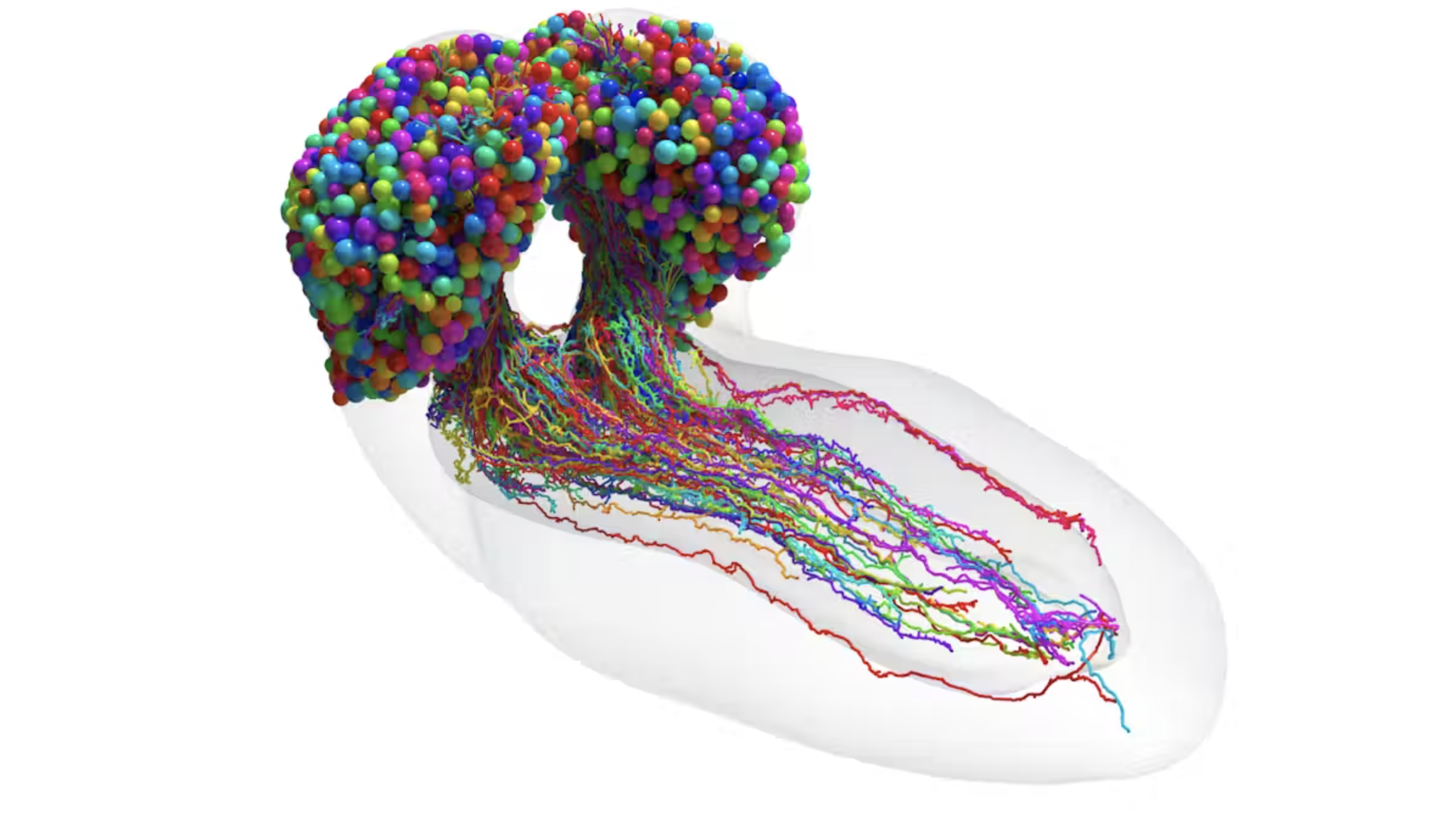

In November of 2022, researchers at Cambridge University and Johns Hopkins University published a preprint of their paper called “The connectome of an insect brain”. It was the culmination of years of work and showed the first ever digital reconstruction of the brain map (connectome) of a complex brain. Painstakingly, the researchers mapped out every single neuron and every single synapse of a fruit fly from a dataset of 4841 electron microscopy (EM) images.

It was a huge endevour and a groundbreaking leap for neuroscientists and biologists, who finally had a complete model of a mind. Creating an algorithm that tracks signals across the brain, researchers got insight into how information moves between neurons and what parts of the brain are responsible for which senses. For example, the researchers discovered that most neurons have many hats, being responsible for many different operations simultaniously. With a bachelor’s degree in cognitive science, I immediately pondered what impact such a neuronal connectome would have on research into human brains. Maybe it could allow us to gain a better understanding of cognitive disseases or genetically maligned neural pathways.

The resulting connectome. Credit: Research article in Science

The resulting connectome. Credit: Research article in Science

My theory was that computational processing could be used to automate neuron segmentation on EM images from human brains more efficiently than human annotation. This is obviously not a novel idea, but perhaps it’s not entirely commonsensical as to why it hasn’t been done yet. Firstly, the fruit fly that was mapped only had 3016 neurons and 548,000 synapses. The human brain, on the other hand, is estimated to contain 86 billion neurons. How many synapses do we then have? Over 100 trillion. To put that number into perspective, there’s about 1000 times as many synapses in our brains as there are stars in the milky way. Google recently performed the largest brain scan ever on a 1 cubic mm large area of the brain. The reconstruction required more than 5000 slices of tissue over the course of a year. What was the size of the resulting dataset? 1.4 petabytes, equivalent to 14 000 4K movies. Extrapolated out then, how much storage would we need to do a full brain scan? 1.6 zettabytes, costing $50 billion and spanning 140 acres, making it the largest data center on the planet – just for a single image.

So how do we process that many images? My approach is to depart from processing 3-dimensional reconstructions as they require too much processing power to process. Instead, I theorised that it would be way faster – and importantly equally accurate – to process each slice separately and then project that in 3D space. But how would the program know that a neuron in one slice is the continuation of the neuron from the last slice? This is where my academic contribution comes in. I hypothesised that we could train the model how to know which parts of a slice are connected by using transfer learning. Transfer learning is a popular technique of machine learning where the knowledge gained from one step is transferred to the next step. A common use case is when you’re building a model that can classify new classes with little or no data, for example when training a computer vision model to recognise a zebra from data on a horse.

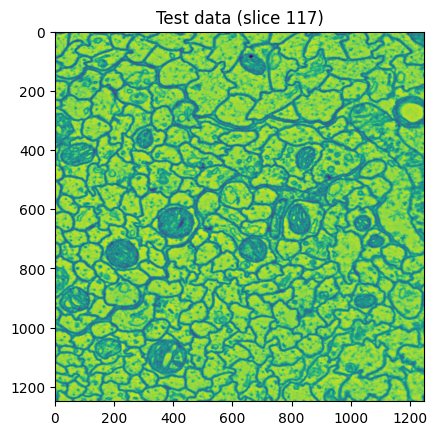

An example of what a slice in my dataset looked like.

An example of what a slice in my dataset looked like.

To prove my hypothesis, I tested the program on a huge dataset of 3D neuron images using my processing technique. After some preprocessing, each 3D image was segmented and a resulting list of neurons was returned. It worked! I also tried to run a 3D segmentation algorithm on the same dataset. The results? My program was almost twice as fast as the 3D algorithm!

Looking forward, the potential applications of this technique are immense. By significantly reducing the time and computational resources required for neuron segmentation, we are opening the door to more extensive and detailed studies of the human brain. This advancement could accelerate research into neurological disorders, cognitive diseases, and the development of more sophisticated brain-computer interfaces. I don’t think this technique will be used on a full dataset anytime soon, as there are many bottlenecks to solve before a human connectome is tangible. That said, I believe new advancements in AI is pivotal to our understanding of the interconnection of human brains. I’m looking forward to seeing where the science takes us.

– Sigurd